AP interview: Colombia to denounce Maduro at UN meeting

BOGOTA — Colombia’s president compared Nicolás Maduro to Serbian war criminal Slobodan Milosevic as he goes on a diplomatic offensive to corral the Venezuelan socialist, warning that he would be making a “stupid” mistake if he were to attack his U.S.-backed neighbour.

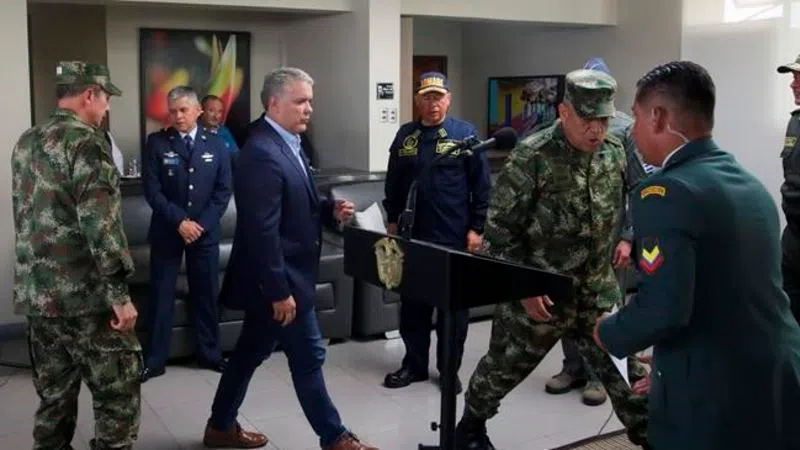

Ivan Duque made the comments in an interview Saturday with The Associated Press before travelling to New York where he is expected to condemn Maduro before the United Nations General Assembly as an abusive autocrat. Duque believes Maduro is not only responsible for the country’s humanitarian catastrophe but is also now a threat to regional stability for his alleged harbouring of Colombian rebels.

“The brutality of Nicolás Maduro is comparable to Slobodan Milosevic,” said Duque, who has called on the International Criminal Court to investigate Maduro for human rights abuses. “It must come to an end.”

While Duque refused to rule out a military strike against the Marxist rebels he claims are hiding out across the border, he said any aggression by Venezuela’s armed forces would immediately trigger a regional response that could include additional sanctions and diplomatic actions.