Rewards for good behaviour part of school-violence prevention: teachers’ union

VANCOUVER — Hearing about the stabbing death of a 14-year-old boy outside a school in Hamilton has Darrel Crimeni grappling with questions of bullying and a lack of empathy that may also have played a role when his grandson’s overdose was filmed and posted on social media.

Crimeni said Carson Crimeni, who was also 14, was bullied relentlessly. On the day he died in August, Carson’s family believes he overdosed after he was given drugs by others who wanted to share his reaction at a skate park in Langley, B.C., on the internet.

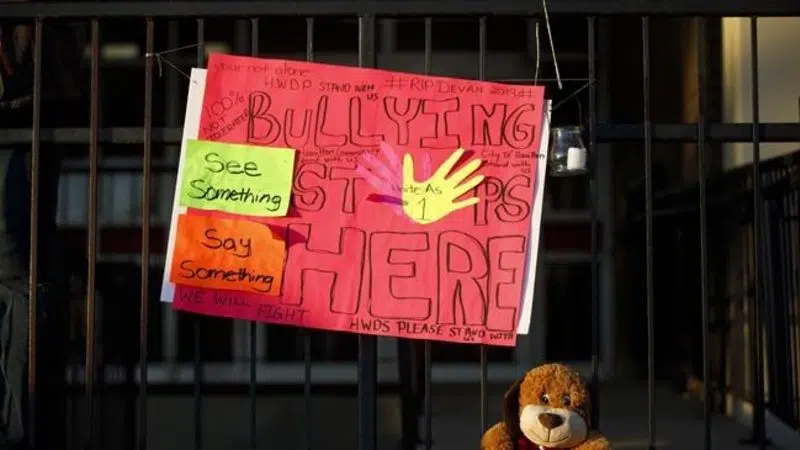

Now, Crimeni is thinking of Devan Bracci-Selvey’s family in Hamilton, knowing they too are struggling to understand their loss, allegedly at the hands of a student who stabbed the boy as he tried to get into his mother’s car last week after calling her to pick him up from school.

“My heart goes out to the mother,” Crimeni said.